Introduction

In

July of last year (1986) at

Present

at the meeting were Professors Jinichiro “Jim” Nakane and Takeshi Nagai of

Jim

Nakane’s presentation was the catalyst which led to the principle of slack

ropes. Nakane reported on efforts to

improve the evaluation of manufacturing performance in

1.

Lead time, the

time to deliver a new order.

2.

The number of

different products producible in a week.

3.

Response time to

a change in total demand.

In

Japanese industry, reported Nakane, there is a tendency to try to measure

plants in a uniform way, and to pursue national goals. Presently, the goal is to reduce lead

time. “We are finding,” he said, “that

as we gain ground … as production lead time is reduced … our quality improves,

our work-in-process inventory decreases, and our total costs also decrease.”

As

background information, Nakane briefly described

The

present Japanese objective, according to Nakane, is to achieve lead times of ˝

to 1/3 of their historical levels.

After

Nakane spoke, the implications of his words began to sink in, and I went to the

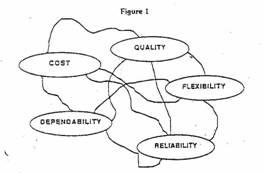

chalkboard and drew this diagram (Figure 1):

There

was a consistency in the Japanese story that I hadn’t noticed before, and I

wanted to know whether I was the only one who’d overlooked it. “Professor Nakane,” I said, “you pursued

quality for thirty years, and saw dependability, flexibility, reliability, and

cost all improve along with it. Now you

shift to lead time, and in pursuing its reduction as the sole focus of your

manufacturing improvement efforts, you are achieving improvements in quality,

dependability and cost, as well.”

“Could

there be a principle at work here? It is

as though you can’t improve just one measure of factory performance, because

they are all linked, as by slack ropes.

Pick an area for improvement, such as lead time, and start pulling on

it. It moves a little, but not far

before something stops it … a tug from another area of performance. Perhaps the work-in-process inventory is so

great that improving lead time on one product causes others to be later,

yielding no net gain. So you turn the

organization’s attention to reducing W.I.P.

And when someone asks, ‘Why are we working on inventory reduction?’ you

respond, “Because it is necessary if we are to reduce lead time, which is our

sole manufacturing goal.” And the

questioner understands, and cooperates, because the importance of reducing

inventory has been made clear. And as

inventory is reduced, lead times can be reduced (and costs come down), but only

until the next rope becomes taut.”

“Perhaps,”

I said, “the key to

“But

we can’t measure just one thing,” commented a participant. “That was the trap we were in when we only

focused on cost. Our efforts at

improving measurements have been to broaden them to encompass quality,

delivery, employee turnover, grievance rates and the like.”

That

remark sparked a lively discussion of the difference between measuring

something and making it an objective.

Are the two necessarily the same?

We can measure to track progress toward an objective, but also must

measure to maintain constraints. Tom

O’Brien said, “We have a saying at GE, ‘You get what you measure.’” Someone replied, “Then measure

everything. The Japanese do, and no

backsliding is tolerated on any performance measure … but improvement is only

sought in one area at a time.

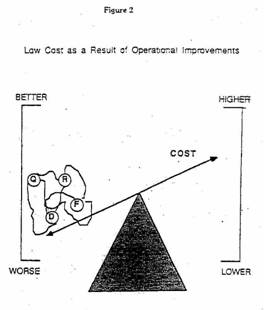

As

a corollary, it was observed that cost reductions, per se, had never been the

goal in Japan, but were usually the explicit goal of manufacturing performance

improvement programs in the U.S. From

this idea came, “Cost is a resultant vector.”

Cost, it would seem, should not be the single purpose. No one could prove that … but focusing on

cost reduction seemed not to have worked in the

AFTERTHOUGHTS

Much

more was discussed at the July meeting which should be written up and aired in

management circles. But it is the slack

ropes idea that has kept nagging at me.

I’ve mentioned it to executives, to colleagues and to students, and they

have been unanimous in their reaction to the effect that I’m not the last to

have perceived the role of singleness of purpose in the success of the Japanese

manufacturing system. So I decided to

prepare this belated report, and now offer a few afterthoughts.

Singleness

of purpose is hardly a new motivational concept. Athletic coaches have long used it to

motivate championship teams. It wins

wars. It builds empires. Is it appropriate to manufacturing

performance improvement? The Japanese

example suggests that it is … provided that the purpose chosen for

single-minded pursuit is one people can pursue with honor, and one that can be

operated on at many levels.

Several

authors have noted that manufacturing performance improvement in

I

am reminded of Wickham Skinner’s concept of “Key Task Focus”. Skinner wrote in his 1974 Harvard Business

Review article “The focused factory” that a factory is inherently limited

by its technology and its management systems, and cannot be “all things to all

people”. Hence, a firm should study its

competitive strategy to determine the most important competitive demands made

on the manufacturing function … and then incorporate those in a Key Task around

which to design and manage manufacturing.

Skinner’s words paralleled the principle of slack ropes when he wrote,

“Not only does [Key Task] focus provide punch and power, but it also provides

clear goals that can be readily understood and assimilated by members of an

organization. It provides, too, a

mechanism for reappraising what is needed for success, and for readjusting and

shaking up old, tired manufacturing organizations with welcome change and a

clear sense of direction.” Doesn’t that

ring true with the Slack Ropes story?

(“Why are we working on inventory?”

“Because inventory is blocking lead time reduction,

our key task.” Oh, that makes

sense!”)

SLACK ROPES VS.

MBO

Another

of my nagging afterthoughts has been the contrast between the principle of

slack ropes and Management by Objectives (MBO) as I have seen the latter

implemented in the

Contrast

that approach with this one: Our organization is good, but must get better if

it is to remain competitive. We will

compete in the future by remaining strong in quality, reliability, and

dependability, but we will increase market share by reducing lead time. That is our goal. All managers and workers will share this

single purpose, and on its achievement we will measure our organizational

success.

Such

an approach is self-organizing.

Initially only the order clerks and production schedulers need act … by

establishing measures of order throughput time and promise performance, and

then shortening promises a bit. But soon

a rope will draw taut, and the organization will follow the taut rope to learn

what is preventing further shortening of lead time, and the problem area thus

located will be worked on next. Perhaps

process quality is still not good enough … or machine set-ups take too long …

or we wait too long for tooling from vendors.

But whatever is the immediate problem, it alone is where we shall focus

our attention. Then we’ll shorten lead

times again, and wait for the next rope to draw taut.

The

management approach implied by the principle of slack ropes seems almost too

simple. No massive data needs. No analytical bureaucracy. Only a well-chosen, competitively essential

goal … and a policy of attacking anything which retards progress, step by

step. Can such an approach work in

OPTIMISM AND

DOUBT

The

principle can work here. In March of

1986 a semiconductor manufacturer in

But

along the way there were many taut ropes, and some interesting second-order

effects. Inspection personnel objected

to the increase in the number of lots to sample. But when told, “We must do this to reduce

lead times,” they cooperated. Second

order effect: same size samples from smaller lots yielded higher outgoing

quality.

The

paperwork accompanying each lot had always been filled out manually at the

stockroom. With so many short lots, this

pencil-pushing became a bottleneck. The

stockroom supervisor located an unused personal computer in the building,

“liberated it”, and the next day the labeling of lots was done with

computer-printed stickers. Second-order

effect: shop employees and customers both found the labels easier to read, and

the error rate was reduced. And thus the

firm followed rope after rope.

I

believe that the slack ropes mechanism will work anywhere that a purpose is

persistently pursued. Therein lies the basis of my optimism. But I have my doubts as to the willingness

and ability of American corporations to adopt and to pursue strategically

critical purposes with persistence. For

thirty years the Japanese followed W. Edwards Deming in pursuit of quality

through statistical process control. The

auto industry in this country discovered Deming in 1980. For a few years thereafter, I’ve been told,

“You could get approval of about anything in the name of quality.” But in the

“This story should have a happy ending. But will it?

You don’t hear so much about W. Edwards Deming these

days in

That

quotation is frightening if, as it suggests, five years is the limit of

consistently pursued purpose in the

DOES WHICH GOAL MATTER?

As

some early readers have pointed out, tagging the central idea of this report a

principle is presumptuous. The

managerial pattern it implies has been seen to work, but only where quality improvement

and lead time reduction have been chosen as goals. It may well be that those two measures of

manufacturing are special. Does it

matter which goal a manger chooses to define as the central purpose? Might some other performance measures behave

as does cost, following but not leading the chain of general improvements I’ve

described? Clearly, those questions and

others require study before the term principle can be properly applied.

General

principle or not, the self-ordering process of improvement in a complex

managerial system implied by the slack ropes idea has kept generating

afterthoughts. My final afterthought is

hopeful. I’ve seen breakthroughs over

the past two decades in

Taken from the O.M. Review, Spring, 1987: “Duncan

C. McDougall is Associate Professor of Operations Management at 2004 Update: Having returned to